ART AND GEOMETRY Part 1 : ITINERARY No. 5 : How geometry informs art, paths through artists and works

E. Agostini | C. Arden Quin | F. Balbo | Bardula | D. Baylon | M. Bedeschi | Bolivar | D. Boriani |G. Bourmaud | E. Careaga | E. Cavallini | N. Costantini | R. F. Frangi | A. Gelmi | MID Group | A. Guzzetti | O. Izumi | M. Massironi | M. Michelazzo | M. Morandini | B. Munari | S. Renko | P. Scheggi | P. Scirpa | J. Stein | J. Toussaint | V. Vasarely | P. Zangara | E. Zucchini

Gallery statement by Monica Bonollo

Valmore studio d'arte presents its 5th itinerary among artists and works chosen and valorised by Valmore in her long career as a gallery owner. Consistent with the gallery's line, which privileges the relationship between art and science, the exhibition is dedicated to the long and fruitful relationship between art and geometry.

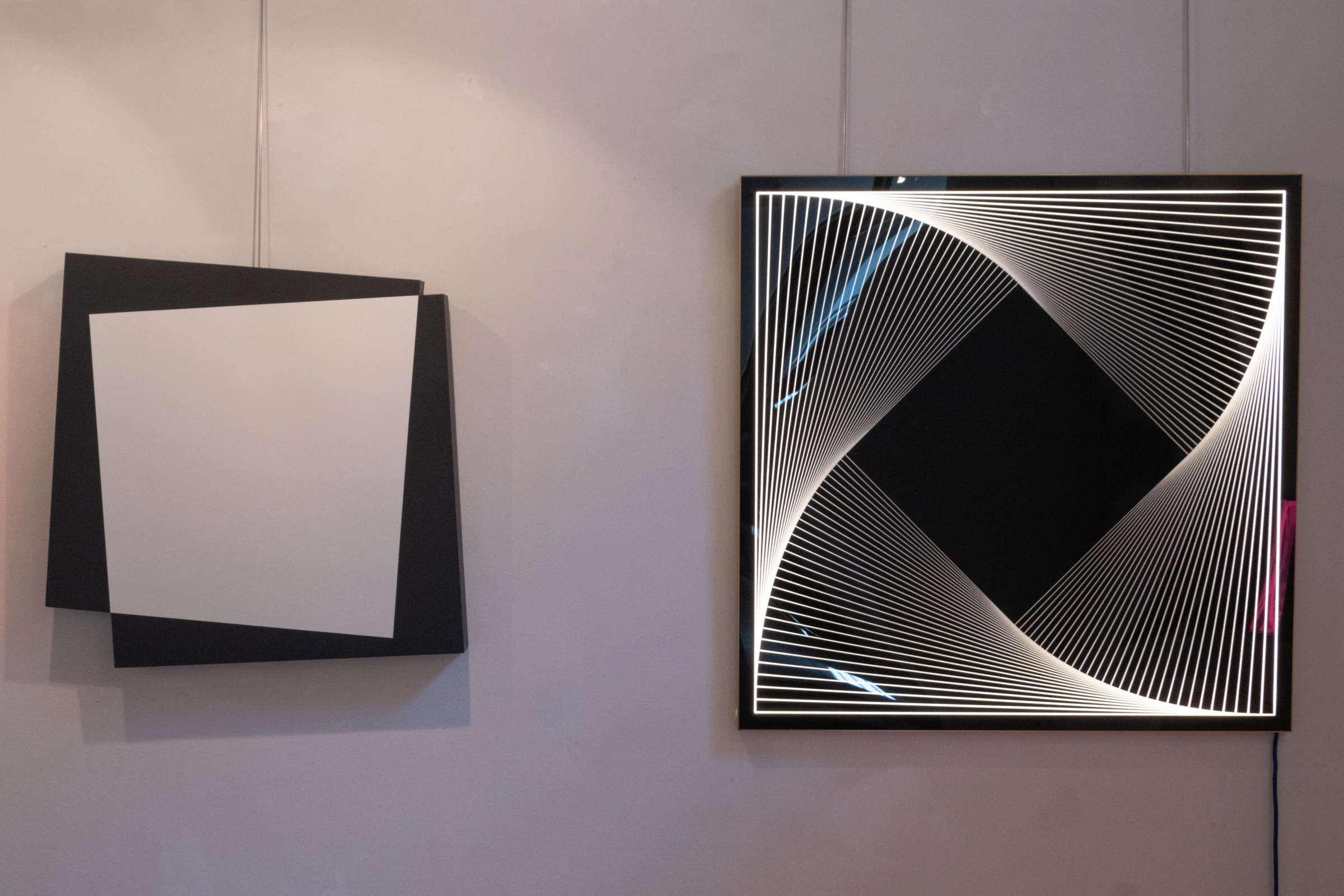

On display are 40 works, including paintings, sculptures and objects, from the 1950s to the present day, by 28 Italian and international artists who share geometry as a tool and language of their research.

The itnerary winds its way through the works of artists chosen from within different movements and research paths that are distant in time and space, sometimes even in theme, but united by the role assumed by geometry, revealing unexpected and sometimes surprising affinities, illuminating the ‘fils rouges’ that run through the rich history of an

important part of international art from the post-World War II period to the present day.

The works start from the 1950s with Vasarely's collages, passing through optical art, international Madi, to light and sound art and interactive and robotic art. The heart of the exhibition is represented by works that we can generically understand within the definition of Geometric Art or Constructivism.

The relationship between art and geometry is as old as the history of art itself, but since the beginning of the 20th century it has been more consciously investigated and deepened, especially by those trends that opposed figurative art.

In the last century, recourse was made to geometry precisely to lay the foundations of a new painting relying on an ‘objective science’, which favours a move away from the representation of the visual reality of the world.

Having exhausted research into the mimetic function of representation, the artists aspired to a more ‘abstract’ art that could favour the different instances of art, no longer aiming at the description of the external world but at the construction of a new society.

The use of geometry in the 20th century is transversal to many different artistic movements, sometimes even in opposition to each other, and this determined the wealth of approaches and interpretations.

The shared objective is the desire to arrive at an autonomous visual composition, freed from an external visual world of reference.

As early as the 1900s, through the first and second post-war years, to the 1960s and the new millennium, several generations of artists have felt the need to create innovative art that incorporates the fundamental changes in technology, science and philosophy, to accompany the social evolution of the world.

To achieve an autonomous visual composition, geometry provides a language, supported by a rigorous deductive logical method, free from external referents and shared by all. This ensures that the subjective element is reduced to a minimum.

Through the simplification of forms (use of squares, circles, triangles, ...) articulated according to mathematical-geometric rules (series, successions, repetitions, translations, rotations, ...), the artists organise constant and variable space elements (e.g. repetition of the same geometric figure with variable size and/or colour, ...).

By experimenting with innumerable series of simple elements combined through countless variables, the artists, in a process much closer to scientific observation than to traditional art practice, achieve their various objectives: maximisation of the reduction of the subjective component, analysis of the mechanisms of vision to interact directly with the eye of the viewer, reflection on art and analysis of its constituent elements, construction of ‘objective and absolute’ art, dismantling of the concept of the artefact/art process.

But the real thread running through this articulate and fertile research pursued over the last century is a rich and multifaceted investigation, alongside that of other ‘exact’ disciplines, into the fundamental concepts of our reality.

What is space? Does time exist? Does time exist without transformation? Is movement real or is it created by our brain? In fact, as Nelson Goodman says: ‘The arts must be taken no less seriously than the sciences as a mode of discovery, of creation, of the expansion of knowledge...’

Monica Bonollo